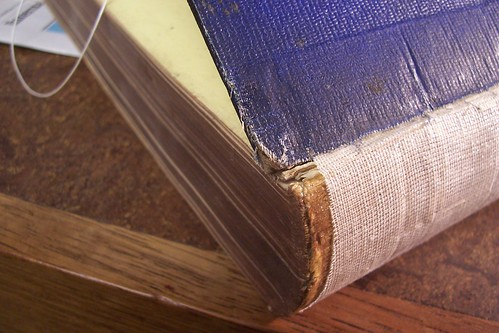

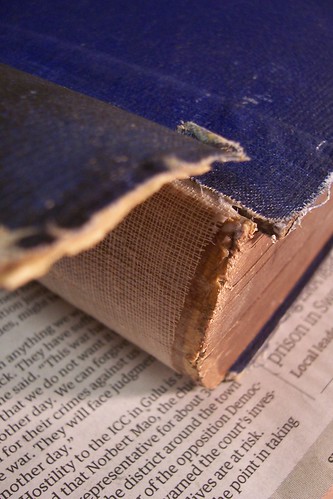

Images of Coptic BookbindingContemporary bookbinders often refer to any non-adhesive bookbinding in which unsupported stitching across the signatures is laced directly into the covers as a "Coptic Binding." ("Unsupported" simply means that the thread passes through each signature and is linked to the identical stitch on the previous signature, rather than being sewn over a cord or a thong. See below for images.) There are a number of tutorials on the web that demonstrate this technique, which can become complicated when sewing on more than three tapes or cords, with more than one needle, or with actual ancient materials (sewing up papyrus is far more difficult than sewing on modern paper).

This is a good basic tutorial on the sewing method, but

this tutorial takes one much closer the sorts of limp bindings we often see in Nag Hammadi and similar finds.

Many images of contemporary "Coptic" binding can be found online, but one of the more interesting collections of such bindings can be seen in the

Special Collections section of the Princeton University Library website. Though most of these images are of relatively late books, the section on

Early Codex and Coptic Sewing and

Early European Sewing and Board Attachment are illustrative of the influence the earliest Coptic bindings had on book technology far into the modern era. The techniques in the "Early European Sewing" section are what characterize "modern" hand-bookbinding, the key difference from their Coptic predecessor being that European bindings introduced a cord or tape onto which each signature was sewn. (If you click on each image, it will take you to an enlarged version with an extremely handy magnifying tool. If only all papyrology sites had the same coding!) You can clearly see the differences in stitching

between this 17th century Ethiopic text (though it is late, it is a very clear example of the Coptic stitch) and

this 15th century English text. The former "Coptic" stitch would be expected in very early Christian manuscripts, and through a scrutiny of these images one can imaginatively retrace the steps of some of our earliest Christian artifacts.

Articles on Coptic BookbindingSuch materials provide an interesting means of reflection on early Christian manuscripts that runs parallel to, and often complete independent of, the related discussion in Biblical Studies. But additional to archives of images, there are also a number of articles on these trajectories in the technology of books written by historians and practioners of book-bindings that highlight an interest direction of scholarship that Biblical manuscript studies has rarely addressed. A report from a 2003 Guild of Bookworkers seminar summarizes a paper given by Dr. John Sharpe on the

History of the Early Codex. This sort of research provides some material depth to a number of questions that have puzzled papryologists and historians of early Christian literature for quite some time:

"The model for the early codex was a wooden tablet. Single-quire text blocks of papyrus bound in simple leather covers with a fore edge flap and a strap for fastening resemble the proportions and shape of many wooden tablets that survived as archeological evidence of the Early Christian Era. The further development of the book structure resulted in the necessity of multi-quire text blocks. Papyrus failed when used for the multi-section structures. Parchment became the material of choice... Covers of wooden boards and leather spines were made separately and attached as “case bindings”. Best examples of early Coptic bindings are books from the Nag Hammadi find (1945, Egypt). A similar single-quire Coptic codex is the Berlin 8502. Leather on its cover is similar to the one used in the Dead Sea Scrolls. It neither resembles tanned leather, nor does it resemble parchment or alum tawed skin. Single-quire text block was not the only codex form during the third and fourth centuries AD. Out of surviving codices from before 400 AD the majority is of the multi-quire type. Early bindings were quite elaborate. They used fringed leather strips that were laced through numerous holes in the board and used as wrapping pieces finished with bone pegs as fasteners. Those early multi-quire text blocks were sewn link stitch and bound in wooden boards with leather spine structures that were assembled separately from the text block and attached in a manner of case bindings. Bindings found under the ruins of the Monastery of Apa Jeremiah near Saqqara (1920) were dismantled and partially described by Lamacraft in 1939."The lack of any consistent method in our earliest extant Coptic bindings suggests that this was still a period of experimentation with this format that expresses itself in the use of different stitching patterns and finishes. It was only with the eventual hegemony of parchment that any sort of standardization set in, as it made the fairly regular stitching of multi-quire text blocks possible. I always assumed on the basis of my very limited first hand knowledge of early Christian papyri that our earliest bindings were "case-bindings," which simply means that the top and bottom leaf of the text block were attached directly to the interior of a leather or stiff paper cover. Sharpe's undocumented point here both confirms my suspicion and raises the question of how related contemporary "Coptic bookinding" really is to its ancestor. Many contemporay definitions of Coptic bookbinding will tell you that the stitching is to be laced directly into the cover (as in the Ethiopic cover above), whereas many early Coptic bindings actually skipped this step and just had the covers glued directly to the endsheets of a textblock. I have always assumed that this latter method would have been the original method practiced by early Christians as it is the least technical and least time consuming process.

Another interesting article from the Book and Paper Group Annual covers the

Adoption of the Codex. Here the "African" model of the early codex is described:

"The model takes two construction types with regard to assembly. The first type is a single quire papyrus codex which can be compared with the single quire parchment notebook from Roman examples. The single quire papyrus codex is associated with a portfolio or wallet like cover made of leather. The text was restitched directly though the cover with interior leather stays positioned in the inner fold to cushion the papyrus from the cinch of the sewing. The cover was frequently reinforced inside with a cartonnage of papyrus. Then, with its protective cover flaps closed and tied with thong, the text was well protected for travel.

The second type was used for binding multiple quires. Each quire was stitched from quire to quire forming chains of stitches across the back of the text. A stitch passing through the inner fold of the gathering would pass to the outer fold connecting the separate folios together. The stitch would then drop down to pick up a previous exterior stitch and climb to enter the next gathering. Quire by quire the book would be constructed. Cover boards, of wood or skin, were also sewn to the text. This "sewn board" book would then be covered with pasted leather and perhaps provided with a second, outer leather case for travel. The result was a secure text block with a docile, flat opening provided by the pliant stitch chains. For the following discussion the African bookbinding model combines together the single and multiple quire type. This obscures the possibility that the sewn single gathering codex may be more associated with the genre of letters folded for travel. The sewn multiple gathering would then be used to accommodate assemblies of letters or larger compilations or, eventually whole Gospels."He next makes a number of interesting points made about the possible technological backgrounds to the codex. While I haven't ever encountered these in Biblical Studies oriented literature on early Christian manuscripts, such points are frequent in literature on this period by historians of bookbinding. Among many others, these two paragraphs are especially intriguing:

The resources of many crafts must have been assimilated into early codex bookbinding. The most apparent parallel to the sewn boards binding technique is found in boat building of antiquity where the shell-first construction method created a hull from sewn boards. The V tunnel lacings connecting the planks and seam battens evoke the whole range of early wooden board book cover attachments. A boat craft connection is also suggested by the role of sea faring trade in materials such as papyrus and by the role of Mediterranean seaports in the production and distribution of manuscripts. Crafts of sewing leather tents and containers would also be relevant. The fourth century Gnostic texts found at Nag Hammadi were generally stitched with leather thongs into leather portfolios.

From the perspective of technology, many comparisons of the scroll and codex format focus on text management features of the two formats. However, during this early period all books, both scroll and codex, lacked text management devises such as word spacing, pagination or punctuation. Only the punctuation of the codex page itself could have played a part in the first century selection of the format. The influence of page format on illustration, as opposed to text, would recommend the codex since iconography could be set off into distinct fields. The African model is relevant here since the tradition of illuminating Christian books was advanced, not by Greek convention, but by the heritage of Coptic art. In pharonic times prayers and liturgies were illustrated with figures of deities and protective symbols in bright colors with boarder designs at the top and bottom. The texts were traced in black outline with catchwords written in red.The connection here between bookbinding and shipbuilding is as intriguing as it is provisional. At the very least, it points out that we can't simply think of the origin of the codex as something that began in a material void, linked only to early Christian theological or missiological particularities. In the course of bookbinding, I often turn to the construction and engineering of other things when I am stumped on a particular sewing or restoration problem. Likewise, early Christians must have sought better ways to put together books, publish their literature, and circulate these documents about the Roman empire. And they most probably turned to other trades and crafts for material solutions to problems in these processes. As the above article points out, this may not just be the case with the codex format, but also with questions regarding ideal page size, ideal text placement and size, and the best means of illumination and punctuation. In this way, the mystery of the origin of the codex is not simply theoretical or social in scope, but is technological and historical.

Coptic Bookbinding and Early Christian OriginsReading an article about early Christian manuscripts by someone from beyond the guild of papyrology and early Christian studies is like having someone else tell you that your shirt is untucked in the back or you have toothpaste on your lip. From the perspective of book technology there are a number of unnoticed connections, unutilized points of access, and simply unknown practical contexts to early Christian fragments that characterize the practice of NT textual criticism. While the historical particularities of this last article could certainly be debated and more sharply defined, it helpfully demonstrates the point I have made consistently elsewhere that there is a lot of space in the material date to begin talking about early Christians as book-binders rather than just book-readers or book-users. There may be enough data out there from early Christian manuscript holdings to enact a convergence between all this data and scholarship from historians of book-binders and the discussion of textual criticism and early Christian origins currently taking place in Biblical Studies.

Update (1/09): Please click the "Coptic Bindings" for additional posts on this subject.